Shirley Baker is only now being recognised as one of the most important female photographers and social documenters of the last century.

The haunting and compelling 2007 documentary of Joy Division, directed by Grant Gee, opens with a montage of images of Manchester in the 70s. It depicts a time of sweeping changes after the post-war streets were systematically cleared of ‘slum dwellings’ and occupants were rehoused in shiny high-rise developments. As became evident pretty swiftly, poverty was not eliminated, merely temporarily masked, and a new, creeping social poverty began to manifest itself.

Joy Division’s sound came into being in this maelstrom of post-industrial upheaval, a legacy of the era of the cotton mills which spread over the city and its satellite towns, a fine layer of dust hanging heavy in the damp Manchester air. In Gee’s documentary, Joy Division’s ambient ‘interior landscape’ coalesces to form the band’s distinctive gritty, moody sound.

Those images remind me of a world captured a decade earlier by Manchester photographer Shirley Baker, whose retrospective is at The Photographers’ Gallery, London, 17th July to 20th September.

Shirley Baker was born in 1932 and was brought up in Manchester. When she was seven or eight, a neighbour bought her and her identical twin sister a present each: a Brownie camera. For Shirley, this was a life-changing moment, her sister recalls how she was mesmerised by the camera and thus began a lifelong obsession. She studied photography at Manchester College of Technology and then went on to teach at Salford College of Art. During the 60s, she became frustrated at being denied a press card, which she interpreted as a result of being woman in a male-dominated industry. At the same time, she became aware of vast changes taking place in Manchester and Salford, and turned her photographer’s eye to capturing the city, its people and communities, realising this was a way of life about to be lost forever. She would wander through the streets alone with her camera, talking to the locals, whom she photographed with a searing honesty and a gentle humour.

The extreme poverty of the times is painfully evident, and some of the images, as Shirley pointed out, look almost Victorian rather than from the 1960s, but these hugely powerful social documents show above all the humanity and pride of the people who lived there. Shirley’s photos are a tribute to the families left living in a kind of limbo, watching houses and streets flattened, wondering when it would be their turn to be rehoused in one of the brand new concrete estates which, by the late 70s, were already falling into a state of decay. Shirley spent enough time in those crumbling streets to become acquainted with the families, and especially the children who would crowd round her, jostling to be photographed. I can understand how she would have been able to gain their confidence; she was always a very patient listener, quietly spoken and never imposing. She would allow whoever she was engaging with to be the focus, and always showed genuine interest in other people. Shirley put people at ease, and managed to make them feel comfortable enough so they no longer noticed this strange woman with her camera in their midst.

My memories of Shirley are of an intensely private person. Being a twin gave her the perfect opportunity to hold back and observe, allowing her naturally more gregarious sister to take the limelight. Her secretive nature was partly due to the fact that she didn’t want to raise expectations. But she needn’t have had concerns, her work was increasingly appreciated throughout her lifetime. What shines through her work is the passion for her subjects; this is what drove her, not fame or a desire for money, indeed this longing for simplicity was reflected in every aspect of her life.

Since the millennium, there has been a growing recognition of the importance of her work – and a realisation of the rarity of female photographers at this time. An exhibition at The Lowry in Manchester in 2000 was an indication of the large body of work she had amassed (the Queen visited, much to the delight of many of the children in the photographs who were present at the occasion); Salford Museum and Art Gallery held an exhibition in 2011, this comprehensive show took in a sweep of work from 1960s Manchester to street life in Camden in the 80s and beyond.

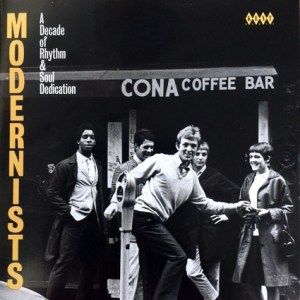

The visual power of her images has led to Shirley’s work finding a place on record covers.

Blackpool-born folk artist Gus MacGregor (below) greatly admired Shirley’s work. He says, “I just find she captures a humour and beauty out of what might otherwise be bleak.” He used several of her works as a backdrop for a series of gigs last year in Bern, Switzerland, and wrote a song entitled Before The Unions Fell which was inspired by her work.

And so it continues… the chequered history of the great northern city still proves to be the driving heartbeat for artists and musicians. Julie Campbell, aka LoneLady, recently released her second album Hinterland, a work inspired by her own north Manchester landscape. See my review of her at Rough Trade East.

Shirley Baker’s upcoming exhibition, ‘Women, Children and Loitering Men’, was in the initial stages of planning when Shirley became ill; the event is now a dedication to this gifted and original artist. Why the title? Is it anti-men? Far from it – it refers to the fact that men were usually out at work, or had been killed in war. The streets were the preserve of women and children, and those men who were present were usually ill or elderly. This exhibition is a powerful, and in some ways shocking, look at a time of upheaval and urban decay which proved inspirational to so many Manchester artists.

Shirley Baker Exhibitions:

Women, Children and Loitering Men by Shirley Baker at The Photographer’s Gallery, 17th July to 20th September 2015

NEW EXHIBITION ON THE BEACH, PHOTOFUSION BRIXTON, MAY 2016

With thanks to Tom Gillmor at Mary Evans Picture Library for his kindness and help. All photography courtesy of Mary Evans Picture Library / Shirley Baker

Fascinating. I really enjoyed this article. Shirley Baker really did produce a body of work that is very special. I come from a poor working class background (though not big city) and its so good to see people portrayed in this way and not as bunch of parasitical chavs – which seems to be so common these days. Really wonderful images and social documentary. I shall have to go on ebay and see if I can find some of her books.

Thanks for your lovely comment and glad to hear you like Shirley Baker’s work. I’m not sure where you are based but you might be interested to hear that there are a couple of exhibitions her work is included in over the next few months. The next one opens on 11th May as part of Photo London at Photo Fusion in Brixton. There may be a work or two at Somerset House as part of Photo London. If you can’t find her books, you could let me know and I can see if I can track one of them down for you.